By Dr. Bruce Andrus

I have been a practicing physician for more than 30 years. During the years I spent as a physician at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, I did some consistent outreach work at Gifford. So, when I made the decision last year that I wanted to focus on clinical cardiology in a more rural setting and try to address an ongoing need, I joined Giffo rd full-time.

rd full-time.

One of the messages I want to convey to the community is that heart disease presents differently in different people. We’re not all the same.

The most common type of treated heart arrhythmia is Atrial Fibrillation, which is often called AFib or AF. I want to share some facts and information about AF as treatment can lower risks and save lives.

What is atrial fibrillation?

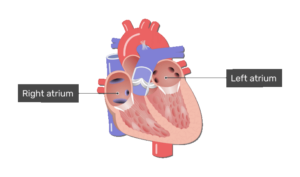

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a relatively common electrical disturbance of the heart that causes an irregular and often fast heart rate lasting more than 30 seconds. The electrical disturbance generally starts in the pulmonary veins where blood returning from the lungs enters the left atrium (Figure 1). It can come and go (paroxysmal) or be continuous (persistent). It may last more than a year (long-standing persistent) or may be accepted as a “new normal” by the patient and physician (permanent). For some, the condition is obvious as they are bothered by the sensation of their heart beating in their chest or experience fatigue and difficulty with physical activity. Others experience no symptoms. In long-standing persistent AF, other regions of the left atrium become involved. A 55-year-old has a roughly 30% chance of AF in their lifetime.

Figure 1(Get Body Smart)

What causes it?

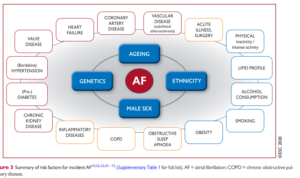

In some, the cause is obvious. In others, it is not clear and is likely a combination of multiple risk factors including:

- Family history of AF

- Older age

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- High blood pressure

- Low blood levels of potassium or magnesium

- Thyroid excess

- Heart valve disease

- Alcohol

- Obesity

- Abnormalities of the heart muscle

- History of heart attack (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Can it lead to a stroke?

Because the heart’s upper chambers are not contracting normally, blood can become stagnant and form a clot. The clot can leave the heart and lodge in a vessel in the brain or elsewhere. The risk of stroke varies from person to person. In general, stroke risk increases with:

- Age

- Congestive heart failure

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Previous instances of stroke or TIA

- Vascular disease

- Mitral stenosis

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Stroke risk is often estimated using the CHA2DS2-Vasc score. Blood thinners such as dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and warfarin dramatically reduce the risk. For those unable to tolerate blood thinners, occlusion devices can be used to “plug” the left atrial appendage where most clots form.

What are the other possible consequences?

If the heart beats more than 120 beats/min for 2 weeks or more, it can weaken and enlarge. It causes uncomfortable palpitations and fatigue with exercise intolerance, due to the loss of coordination of the upper and lower chambers. Over time the upper chambers can enlarge and there is an increased risk of heart failure. However, this is generally reversible

What are the 1st steps to managing AF?

- Search for and correct treatable causes

- Consider the risks and benefits of blood thinners

- Control heart rate if too fast

Rate control versus rhythm control?

Rate control refers to accepting atrial fibrillation as a new normal but keeping the heart rate under control (not too fast or slow). Rate control is much simpler and is often chosen by patients who have minimal symptoms, advanced age, multiple chronic medical conditions and a high likelihood of recurrence.

Rhythm control refers to trying to restore normal rhythm (sinus rate) by maintaining it using medications or catheter ablation targeting the pulmonary veins. Rhythm control is often chosen by patients and physicians for younger patients who have had a recent onset of atrial fibrillation, persistent symptoms despite good rate control and a good chance of successfully controlling the heart rhythm. Regardless of the rate or rhythm control choice, anticoagulation remains an important consideration.

How can sinus rhythm be controlled?

If the AF is persistent, direct current cardioversion under anesthesia is generally used to “reset” the heart. This is an electric current delivered in synchrony with the heartbeat.

Options to maintain normal rhythm include medications and catheter ablation in an electrophysiology (EP) lab.

Medications

- flecainide

- propafenone

- dronedarone

- dofetilide

- sotalol

- amiodarone

Catheter ablation

Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is performed using cryoballoon catheters or radiofrequency energy. An evolving new technology is pulsed-field ablation (PFA), a nonthermal technique not yet in routine clinical use. These catheter techniques seek to electrically isolate the pulmonary veins so impulses arising from the pulmonary vein do not reach the rest of the heart. Catheters are inserted through the femoral vein and advanced to the right atrium and across the intra-atrial septum to the left atrium under x-ray guidance.

Recent studies suggest that catheter ablation may provide better control of atrial fibrillation with fewer hospitalizations and less progression to permanent atrial fibrillation compared to medications. However, not all patients may want this or be good candidates due to their overall medical condition.

Working with your medical team

There is not one approach that’s best for all patients with atrial fibrillation. Every patient has a unique combination of medical history, experiences, expectations and priorities. Not every decision needs to be made immediately. There is time to consider options and if one approach is not working, another can be pursued.

We have a great team here at Gifford. I work closely with Leslie Osterman, PA-C and we have an excellent cardiology nurse in Emily Russell. If you have questions or concerns about AF or any other issue pertaining to cardiovascular medicine. Please give us a call at (802) 728-2430.